By Gherardo Bonini*

When the Panathenaic stadium in Athens on 7 April 1896 hosted the first Olympic competition for weightlifting, only few athletic circles in few countries practiced this sport internationally. The standardization of sports progressed slowly. In weightlifting, the difficulties were remarkably accentuated, because styles of lifting, sizes of tools, rules and procedures were very different if not between country and country, then between different geo-political areas.

The Athens Games, for example, had favored the French system that provided for a single stop at shoulder level (without allowing the bar to touch the shoulder) for the basic one-handed and two-handed tests. In Athens, two events took place and they were comparable both to the exercise of jerk – where the athlete stopped the weight at the shoulder level, from where he pushed the tool in the air with a forceful and rapid movement, moving also the legs. In the two-handed event, the Dane Viggo Jensen won by lifting 111.5 kilograms – the same amount as the Brit Launceston Elliot, but being awarded the victory by the jury due to his better style. Elliot then won the one-handed event, lifting 71 kilos against Jensen’s 57.

Before analyzing the competitive value of the weightlifting competition at the inaugural Olympic Games, it seems appropriate to mention the other classic movement of the French school – namely the clean and press, in which the athlete, without moving trunk or legs, slowly raised the tool above the head. In any case, no French athlete participated in the Athens Games. The main athletic clubs in Lille and Roubaix were far from de Coubertin’s Union des Societes Françaises de Sports Athletiques (USFSA) amateur positions. In the few competitions held before the Games, the results of the best athletes, for example Marcel Marchand, winner of the Northern Championships in 1894, were better than those achieved in Athens.

In Italy, weightlifting had appeared in 1890 as part of gymnastic festivals and it followed the French procedure. A few years later, the thriving Milanese Athletic Club, founded by the Marquis Luigi Monticelli Obizzi, became a member of the German athletic federation, founded in 1891, which had organized the first amateur national championship in the world in 1893.

In Germany – but also in Austria, Holland, Russia and Sweden – the style practiced was called Continental in the years to come. In the two movements of jerk and press, the German athletes made the tool stop at their waist before another rest at the shoulder. In the so-called one-handed exercises, the athlete brought the tool to shoulder height in a time, but with two hands, then overhead with one arm. The snatch, namely from the ground direct to overhead, was rarely practiced. Therefore, the Milanese Athletic Club spread the Continental style in Northern Italy. The differences between styles were significant.

Splitting the effort between two rests – one at the waist and one at the shoulder level – instead of one, typically allowed lifting heavier weights; however, since Continental athletes rarely tried the French style, it was not clearly understood how much advantage the Continental style brought.

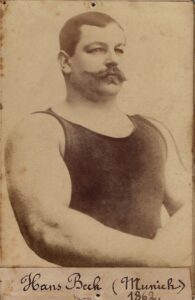

On 9 March 1896, the German Hans Beck – national champion in 1895, third-placed in 1893 – won a European title arbitrarily offered by the Hercules club in Rotterdam. The competition there consisted of three tests – two-handed jerk and press in Continental style, respectively, and a resistance test in press with a weight of 70 kilos. Beck jerked 135 kilos and his countrymate Schöns 134. On 5 April that same year, another Dutch club, Amsterdam’s Hollandia, organized a world championship – this time comprising four tests, adding a two-handed endurance test. The organizers calculated the classification not with a total of lifted kilos, as in force in the German championships, but by assigning points.

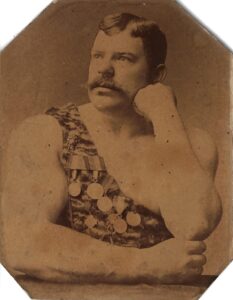

Another German national champion emerged in Amsterdam – Johannes Schneider of Cologne, winner in 1893 and second in 1895 behind Beck. In the two-handed jerk, Schneider lifted 120 kilos. At the end of the year, in the weightlifting contest within the framework of the Italian Gymnastic Festival in Rome, he lifted 130 kilos in the same discipline. Thus, in the 1896 season, by winning two events with high resounding titles, albeit unofficial, the German school had confirmed its dominance in the early years of the sport. The German sports movement, strongly influenced by the gymnastic one, was not interested in sending its athletes to Athens, among others due to harboring strong reservations about the organizational and competitive quality of the Olympics. Only thanks to the interest of the manager Willibald Gebhardt some gymnasts of the Berlin area took part in Athens. As it was also the case in Italy and France, the gymnasts of the time were well-trained in numerous other sports, including wrestling and weightlifting. And one of these athletes, Carl Schuhmann of the Berliner Turnerbund – Olympic champion in both gymnastics (vault) and wrestling – participated in the two-handed jerk contest. Moreover, in the 1896 season, the Swede Arvid Andersson, anchored to the Continental style, also stood out.

The Brit Edward Lawrence Levy – winner of an unofficial world championship organized in London in 1891 – was part of the weightlifting jury in Athens. Despite a general lack of interest in the Olympics in Great Britain at the time, Levy – just like the eventual Olympic champion Elliot, a debutant in 1891 and then English champion in 1894 – was probably convinced to travel to Athens by Lord Astley, organizer of aforementioned competition in 1891, and responder to de Coubertin’s call in the Sorbonne Congress of 1894. Besides Jensen, Elliot and Schuhmann, the Greeks Versis (third place in the two-handed lift), Papasideris and Nikolopoulos (third place in the one-handed lift), and the Hungary-based Serb Topavicza competed in Athens. In addition to the French athletes, the Athenian weightlifting events lacked Austrian, Belgian, Dutch, Italian and Russian representatives.

In particular, Austria did not send lifters. The best Viennese, Wilhelm Türk, credited with performances compatible with the French style superior to those of the best Olympians, would not have been eligible to participate due to his past (1893-1895) as a professional. Like other competitions, for example in swimming and rowing, the Olympics were not the supreme weightlifting championship in 1896. The name Olympiad was not enough to arouse interest. In addition to economic problems, there were regulatory issues, as exemplified by weightlifting.

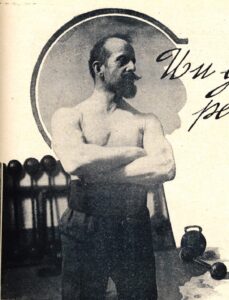

How to evaluate the Athens performances? Probably, the achievements of Beck, Schöns, Andersson and other athletes surpassed those of the Olympic champions Jensen and Elliot. Like Türk, Beck too achieved rare, but strong and noteworthy performances compatible with the French style. The main European newspapers knew the real standards of the sport. Overall, weightlifting, like most other disciplines featured at the inaugural Olympic Games of the modern era, did not figure in ancient Olympics. And being a new international sports event at the time, the 1896 Olympics were not on the radar of the top-level weightlifters of the day.

Of the Athenian group of Olympic participants, only Elliot continued to shine in weightlifting in the following years, later transitioning to professionalism. The other protagonists of the Panathenaic took advantage of the opportunity to obtain unexpected results.

Photos courtesy of Michael Murphy

* Gherardo Bonini

Gherardo graduated from the University of Florence after reading Moral Philosophy and also holds a Diploma in Archival, Paleography and Diplomacy from the State Archives of Florence, which he achieved in 1991. He has worked in the Historical Archives of the European Union since 1989 and since 2013 has been deputy director. His main area of study is European Sport between 1815-1945 with special emphasis on Austrian sport, weightlifting and swimming. His most recent book “Otto Herschmann und die Olympische Bewegung: Die Etablierung des modernen Sports in Österreich”, about sports pioneer Otto Herschmann (1877-1942) and the establishment of modern sports in Austria, was published by Löcker in 2021.